The CIO Monthly Perspective

ENERGY, SECURITY, GROCERIES

Time to focus on Main Street’s ESG

We are more than two decades into the 21st century. Hitler, Stalin, and Mao have been dead for so long, yet the hubris of a few egomaniacal dictators can still inflict so much injustice and damage to so many. Putin’s war on Ukraine has resulted in flagrant atrocities, and its disruptions to global food and energy supplies have increased the risk of humanitarian crises in some countries. His comrade Xi has been so obsessed with making zero-COVID a manifestation of the CCP’s superiority that he turned Shanghai, China’s pride and financial center of 26 million residents, into a virtual prison where more people have died from suicides and lack of food and medical access than from the Omicron variant. Beyond the suffering of people directly affected by these irrational actions, the world economy has been taken hostage as inflationary pressures and supply chain disruptions are likely to persist longer.

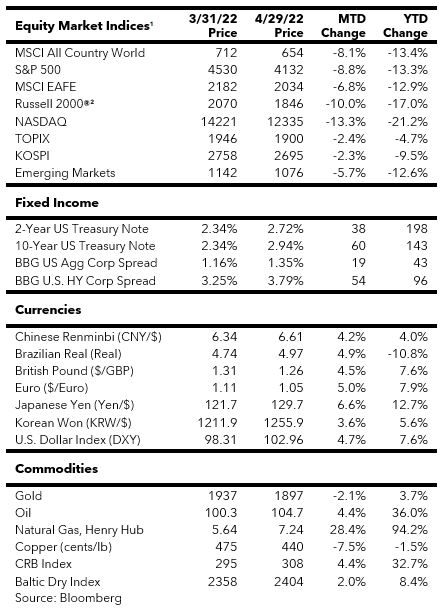

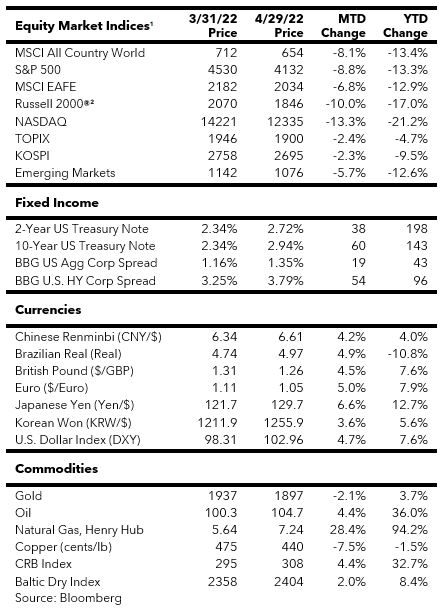

These twin issues of Putin’s war and Xi’s lockdowns coupled with a more hawkish Fed have forced investors to recalibrate risk premia for various financial assets. It has been a rather difficult start to the year as fixed income and equities have both suffered sizeable pullbacks, which is an unusual combination. Investors have now priced in three consecutive 50-bps Fed funds rate hikes for the upcoming FOMC meetings. The market’s forecast for the Fed Funds rate by year end has risen from 0.82% at the start of 2022 to 2.82% today. Widening interest rate differentials between the U.S. and other major economies have sent the U.S. Dollar Index soaring to the highest levels in nearly two decades; the greenback gained 5% and 6% vs. the euro and the yen, respectively, in April alone. The U.S. dollar’s rapid rise will not only hurt U.S. multinational’s overseas businesses, which were already pressured by various disruptions, but also increase the systemic risk in the global financial system. Lastly, market liquidity will likely get tighter as the Fed starts to shrink its bloated balance sheet.

The receding tide of liquidity has hurt the value of a non-fungible token (NFT) linked to Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s first-ever tweet. It was purchased by a crypto entrepreneur for $2.9 million in March 2021 and put up for auction last month with the promise to give 50% of the proceeds of $25 million or more to charity. Well, recent market declines must have made speculators less charitable as the highest bid for that NFT was reportedly just $277. Instead of buying that meaningless tweet, Elon Musk cinched a $44 billion deal to take Twitter private with the objective of restoring free speech on the platform. The prospect of censorship removal turned out to be deeply triggering to some, but as Musk wryly tweeted, “The extreme antibody reaction from those who fear free speech says it all.”

A LOVE STORY

She was born of nobility in Prague in 1843. Shortly before her birth, her father, hailed from the prominent House of Kinsky, passed away at age 75. He left baby Countess Bertha Kinsky and her mother, who was only in her mid-20s at the time of his passing, a modest income and limited financial resources. Bertha enjoyed a cultured upbringing and exceled in literature, piano, and singing. She was also proficient in several languages. Unfortunately, her mother later lost their limited wealth to gambling, which led Bertha to be betrothed to a prosperous publisher who was a member of a wealthy German banking family. Bertha eventually broke off the engagement as she was repulsed by the prospect of marrying a man 31 years her senior.

Despite her reputation as a great beauty, and having been courted by nobles and princes, Bertha was still single at age 30 when she found employment as a governess to the four daughters of Baron von Suttner in Vienna. She soon became romantically involved with the girls’ elder brother Arthur, who was seven years her junior. Arthur’s parents disapproved of this relationship and asked Bertha to find employment elsewhere. In 1876, Bertha answered a newspaper ad that read, “A wealthy, cultured elderly gentleman seeking lady of mature age, versed in languages, as secretary and supervisor of household.” The ad was placed by Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, who was then 43 years old. They hit it off very well and Alfred hired Bertha on the spot. Alfred, a shy and introverted man, may have subtly made a romantic overture to her, but Bertha missed Arthur. Her brief stint working for Alfred ended when she received a telegram from Arthur asking her to marry him. Arthur was disinherited by his parents after the marriage, so the newlywed couple moved to present day Georgia, which at the time was part of the Russian Empire, to get a fresh start.

Life in Georgia was not easy for Arthur and Bertha. They faced poverty and social isolation but managed to blossom into respected journalists covering ethnic conflicts in the Caucasus. Bertha and Alfred remained friends via correspondence, which often touched on her favorite subjects of disarmament and peace. It was an odd friendship as Bertha was gradually becoming one of the leading voices in Europe’s peace movement, while Alfred was amassing a great fortune as an arms merchant. His invention of dynamite had revolutionized warfare and made conflicts more deadly. In the last decade of his life, Alfred became even more obsessed with weapons development. He argued to Bertha that lasting peace can only be achieved with the threat of what we now call mutually assured destruction, or MAD for short. “Perhaps my factories will put an end to war even sooner than your peace congresses,” Alfred once boasted to Bertha, “On the day when two armies will be able to annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will recoil with horror and disband their troops on knowing that total devastation will be in store for them if they engage themselves in war.”

In 1888, Ludvig Nobel, one of Alfred’s brothers, suddenly died while visiting Cannes. A French newspaper got mixed up with the identity of the deceased, believing that it was Alfred. The paper allegedly published a scathing obituary titled, “The Merchant of Death is Dead,” and condemned his war profiteering. Alfred was horrified to learn what a vile figure he would be remembered as. This realization drove him to rethink how he could leave a positive legacy but did not make him scale back his arms business.

A year later, Bertha published her seminal work, Die Waffen nieder! (Down with Weapons! or Lay Down Your Arms! in the translated English publication), a novel about an Austrian countess’ experience and personal tragedies over four wars in a span of 12 years. To the surprise of many publishers who had turned down this novel, the book was a smash hit and ran twelve editions in the first six years. It was eventually translated into 12 languages and energized the pacifist movement in Europe. Alfred called the book a masterpiece and praised Bertha as “an Amazon who so valiantly wages war on war.”

The two friends last met in August 1892, when Alfred accepted Bertha’s invitation to the fourth Universal Peace Congress in Switzerland, which he attended incognito. Alfred asked Bertha to keep him abreast of the peace movement and promised to support it financially. A year later, Alfred began to formulate the idea of the Nobel Prizes in his will, which was finally completed and signed in November 1895. The prizes would cover Physics, Chemistry, Medicine, Literature, and Peace, the last of which he had debated with Berta over what efforts should be rewarded.

In his last letter to Bertha three weeks before his death on December 10th, 1896, Alfred said he was enchanted to see the peace movement gaining ground and thanked Bertha for holding an “exalted rank” in leading the effort. When his final will and testament was read on December 30th, many were shocked that he had bequeathed 94% of his assets to fund the Nobel Prizes. It took his executors several years to realize his vision, and the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901.

Bertha lost her pacifist comrade and husband Arthur in 1902 but continued to travel tirelessly for the peace movement. In 1905, Baroness Bertha von Suttner became the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her “audacity to oppose the horrors of war.” In the final months of her life in 1914, though stricken with cancer, she was still organizing the 21st Universal Peace Congress to be held in September of that year. She died on June 21st, seven days before the heir presumptive to her country’s throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. Exactly a month after the assassination, the world was plunged into hitherto the worst military conflict known to mankind. Needless to say, the September 1914 peace congress that Bertha had worked on right up until her death was never held.

HOW PEACE WAS WON

Alfred and Bertha’s goals were largely achieved, at least in Europe, several decades after their deaths. Alfred’s vision of a weapon of total devastation was realized on July 16, 1945, with the first detonation of the atomic bomb in the barren desert of New Mexico. Four years later, the Soviet Union also successfully tested the bomb in Kazakhstan. The threat of mutually assured destruction had indeed prevented direct military conflicts between the two powers even though there were many proxy wars elsewhere. In fact, if not for NATO’s nuclear deterrent, the Soviet Union might have turned the Cold War into a hot one given its overwhelming edge in conventional forces. Today, despite Russia’s atrocities in Ukraine, the West has avoided direct confrontation with Russia because of Putin’s nuclear arsenal.

Two destructive wars that killed well over 100 million people in the first half of the 20th century convinced Western Europeans to seriously work on preventing future military conflicts. In 1946, Winston Churchill advocated the creation of a United States of Europe as an antidote to extreme nationalism and militarism. France was keen on creating a tight economic union with West Germany to make war between the two countries, “not only unthinkable but materially impossible,” according to former French foreign minister Robert Schuman. These economic and political integration efforts eventually evolved into the European Union, which has grown to 27 member states today.

West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), was arguably the biggest beneficiary of America’s nuclear umbrella, military protection, and economic partnership. The word Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”) was used to describe the rapid rise of its economy from the ashes of WWII. As the FRG became more prosperous and self-confident, its foreign and economic policies started to diverge from that of its principal benefactor. In 1969, the left-leaning Social Democratic Party (SDP) came into power and pursued a dovish policy of Ostpolitik – greater engagement and normalization of relationship with Eastern Europe, especially East Germany. Ostpolitik was initially supported by the Nixon Administration, which was promoting détente with the Soviet Union. However, the FRG was reluctant to join President Jimmy Carter’s effort to tie human rights to the West’s engagement with the Soviet Union. Détente collapsed in late 1979 after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, which Carter called “the greatest threat to world peace since the Second World War.” The U.S. imposed harsh sanctions on the Soviet Union, but the FRG sought to preserve Ostpolitik and only reluctantly joined the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics.

The tension in the Western alliance came to the forefront in the 1980s. Reagan’s policies of rearmament and containment were anathema to the West German intellectuals and populace. Instead of faulting the Soviet Union for its decades of human rights abuses and the subjugation of East Germany and other satellite states, they blamed America as the aggressor, polluter, warmonger, and profiteer. Anti-Americanism gave rise to the Green Party, which led massive protests against American military presence and sought to make the FRG a neutral nation. The FRG also butted heads with the U.S. over trade policies – the former insisted on providing the Soviet Union with financing, commerce, and technology transfer under the motto Wandel durch Handel (“change through trade”), but the latter viewed trade as a geopolitical leverage. The FRG also led the effort to help the Soviet Union construct pipelines to tap into the vast natural gas reserves in Siberia. The Reagan Administration warned that the gas pipeline deal would bankroll the Soviet Union’s aggression and put Western Europe’s energy security at risk. This tussle led to U.S. sanctions against European companies involved in the pipeline project, which triggered severe blowback from Europe. In the end, President Reagan uncharacteristically backed down in order to preserve the alliance.

The risk of widening rifts in the Western alliance was more than offset by the rapid deterioration of the Soviet economy. Reagan’s hawkish policies were eventually vindicated by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the disintegration of the Soviet empire. However, some pundits, especially the pacifists, still argued that it had taken a confluence of factors, including Ostpolitik that supposedly softened East Germany’s edge, to bring down the Soviet bloc without a shooting war in Continental Europe.

SHAPING THE WORLD THROUGH DAVOS

The collapse of the Soviet Union left America as the world’s unipolar hegemon. However, in the absence of a common geopolitical threat, national security was put on the back burner while the promotion of trade and business interests became the focus of foreign policymaking. Western Europe, having been the junior partner to the U.S. for nearly 50 years, saw an opportunity to become America’s equal with the creation of its own political, economic, and currency union. The fall of the erstwhile “Iron Curtain” also provided it with new markets, as well as cheap commodities and labor. This European reassertion suddenly propelled a bespectacled, balding professor and his brainchild to a pole position in shaping global consensus ranging from ESG (environmental, social, governance) to the new world order.

In 1971, Klaus Schwab, a 32-year-old business professor at the University of Geneva, started running an annual business conference called the European Management Forum in Davos, an Alpine resort town; it was an ideal setup for corporate executives to network and relax. In 1981, TIME dubbed it a “Magic Meeting Place” that offered its attendees “a delightful vacation on the expense account” at one of Europe’s most fashionable ski resorts. In 1987, Schwab changed the name of the conference to the World Economic Forum (WEF) as he positioned it to deal with international issues on multiple fronts.

Like his German compatriots who had been eyeing opportunities in Russia, Schwab was quick to foster good relationships with Russian elites post-Soviet Union. It was a marriage of convenience – since the 1990s, Russian oligarchs coveted the invitation to the WEF as the ultimate stamp of global legitimacy, and the WEF received generous support from the nouveau riche who had money to burn. Putin and his political ally, Dmitry Medvedev, have spoken at the Forum five times between 2007 and 2021. The WEF had even invited Putin to speak at the 2015 gathering despite Russia’s blatant annexation of Crimea in the previous spring.

Schwab was also prescient about opportunities in China. He had the foresight to invite Deng Xiaoping to the forum in 1979, and China has been sending official delegates to Davos ever since. In 1989, despite Western boycotts against Beijing for its brutal suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests, the WEF still held its Business Leaders Symposium in China under the guise of bridge-building. Three years later, the WEF again defied Western sanctions by having Chinese Premier Li Peng, known to some as the “Butcher of Beijing” for his role in the Tiananmen crackdown, speak at Davos. Schwab’s embrace of China was amply rewarded as Chinese elites and companies have flocked to Davos like their Russian peers.

Over time, the forum in Davos evolved into ostentatious festivities of the moneyed class – billionaires, corporate chieftains, celebrities, and the privileged from authoritarian states – for networking, deal making, and virtue signaling. A recent op-ed in Vanity Fair observed that Schwab has masterfully meshed two irreconcilable positions at once: “He blithely disregards the obvious contradictions between the pristine values he publicly champions – inclusion, equity, transparency – and the unsavory compromises that he makes in wooing people with money and influence.”

These contradictions reflect the reality that the balance of economic power has been gradually shifting in favor of resource-rich countries – many of which are authoritarian – and a more assertive China. Western elites have profited handsomely from doing business with unscrupulous entities in these countries, public and private, under the guise of change through trade and bridge-building. Some would argue that the interdependency is a necessity, especially for Europe, which does not possess any differentiated comparative advantages when compared to other major economies. Indeed, the U.S. has the edge in technology, military might, and shale energy, not to mention the global reserve currency. China is the world’s most efficient manufacturer and has the economy of scale. Russia leads the world in natural resource exports – oil, gas, grain, timber, etc. Europe is squeezed in the middle – it depends on the U.S. for defense, subsists on Russian energy, and is addicted to China’s cheap labor and big markets. Where Europe excels is the allure of old money, cultural heritage, luxury brands, and the rule of law – magnets to Russian oligarchs, Chinese tycoons, the nouveau riche around the globe.

While Europe may not be highly regarded for its economic or military prowess, it does retain an edge through venues such as the Nobel Prize and the World Economic Forum to position itself as the conscience of the world on ESG issues such as human rights, climate change, the global reset, etc. Some European think tanks believe that Europe can turn its proselytizing of ESG and climate initiatives into a comparative advantage. Decarbonization is viewed as a tremendous opportunity for their companies to get a leg up on the rest of the world. European policymakers also believe that regulatory imposition of their ESG criteria – non-financial performance metrics – will make their companies more resilient, sustainable, and competitive. Some have even advocated for exporting Europe’s ESG taxonomy and standards as a soft power to reshape global norms and curb unruly behavior. In short, thirty years of common market development and relative peace have given many European policymakers, NGOs, and academics a sense of moral superiority to attempt transforming the world with their ideals.

RETHINKING ESG

Despite rigorous work on corporate resiliency and sustainability, ESG evangelists and Europe’s elites collectively overlooked their biggest vulnerability – their dependency on Russian energy, something the Gipper had forewarned as early as 40 years ago. It seems that European leaders and geopolitical experts had simply refused to believe that Putin would attempt to do to Ukraine what he has done to Crimea just eight years ago. Or perhaps they were planning on looking the other way, like they did with the Crimea annexation. Nowhere in the World Economic Forum’s “Global Risks Report 2022” – released with much fanfare in early January – was the risk of a Russian invasion mentioned. The report’s top ten global risks for the next 10 years were: climate action failure; extreme weather; biodiversity loss; social cohesion erosion; livelihood crises; infectious diseases; human environmental damage; natural resources crises; debt crises; and geoeconomics confrontation. These are no doubt clear and present dangers, but the experts somehow managed to miss the biggest elephant, or bear, in the room.

Now that the horse is out of the barn, there are growing calls for Europe to go cold turkey with Russian natural gas. However, doing so would create even stronger stagflation pressure reverberating across the globe. As Martin Brudermüller, the CEO of German chemical giant BASF, admitted recently, “Russian gas is the foundation of German industry’s global competitiveness.” There is the risk that Russian natural gas might turn out to be the wedge that breaks the unity in Europe’s sanctions against Russia.

The failure to anticipate Europe’s vulnerability to Russian energy has stirred up some soul-searching and finger-pointing in the ESG community, which has long touted the superiority of its comprehensive analyses in risk identification and mitigation. Instead, Putin’s war has shown that the E, S, and G that affect ordinary people are energy, security, and groceries.

If we are honest with ourselves, we should ask if the West’s anti-nuclear and anti-fossil fuel movements have exacerbated the current energy crisis. To wit, on the last day of 2021, while Putin was building up troops along the border with Ukraine, Germany shut down three of their six remaining nuclear power plants. Today, it is still on track to decommission the last three plants by year end. In March 2020, Congressional Republicans proposed a $3 billion purchase of crude oil following Trump’s directive to fill the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) “right to the top” in the face of collapsing crude oil prices. However, Senate Democrats nixed the bill on the grounds that it was a bailout for the oil industry. Well, the $3 billion could have funded, on the cheap, nearly half of President Biden’s emergency 180 million barrels of crude oil release from the SPR. It’s also ironic that politicians who have long campaigned on sharply curtailing U.S. oil production are now accusing oil companies of not producing enough. Do they realize that companies are unwilling to make capital investments in long-cycle projects in the face of regulatory threats that would make them obsolete in the not-too-distant future?

Putting aside political grandstanding and dogma, the world needs pragmatic energy policies. While many will rightly seize the energy crisis to accelerate the adoption of renewable energy, the intermittent nature of solar and wind energy cannot be relied on to power all of the electrical vehicles and crypto server farms in modern cities. The modern economy depends on steady, continuous energy generation – so-called baseload power – from fossil fuels, nuclear, hydro, or geothermal means. As a partial replacement for Russian energy, Europe has agreed to sharply increase its purchase of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG). It will require tens of billions of dollars of investment to expand the infrastructure, which includes liquefaction facilities, pipelines, etc. It remains to be seen if ESG-minded activists will try to block some of these projects as they have in the past, and whether they will stop vilifying financial institutions for lending to the fossil fuel industry. Nuclear power, a zero-emission and cheap source of energy, is another viable solution but needs to overcome opposition from environmentalists in many countries.

On the security front, the West is now learning the hard way that national security is linked to not just the military, but also energy, supply chain, cyberspace, media, and overall, the economy. Just as Europe’s coddling of Putin has led to the current energy crunch, Western businesses’ decades of manufacturing outsourcing and technology transfer to China have left us alarmingly vulnerable on so many fronts. What will happen to the supply of iPhones, rare earth minerals, and even antibiotics, should a conflict between the West and China lead to mutual sanctions? ESG investors should channel the zeal they exhibited in demanding corporate carbon footprint disclosures to ask companies to report their supply chain dependencies on China and how they plan on reducing them. Businesses left to their own devices have little incentive to reduce their profitable dependency on China. In fact, China has long counted on Western business executives to be their best lobbyists. ESG investors can play a big role under the banner of building sustainable businesses to nudge companies to rework their supply chains. Imagine the positive economic and moral impact if Apple, as one of the most admired and influential companies, starts a multi-year transition to re-shore its supply chain to democratic countries. Of course, bringing manufacturing back home requires reliable and cost-effective energy supply, which affirms the reality that energy security is national security.

The “G” in ESG, for folks on Main Street, is affordable groceries to feed their families. The ESG community has been working on well-intentioned projects such as alternative proteins, nutrition-related issues, biodiversity loss minimization, etc. However, what they do with fossil fuels has considerable impact on the food supply chain – natural gas as the main feedstock for fertilizers, propane to run farm equipment, dryers, generators, irrigations pumps, and petroleum for packaging and transportation of foodstuffs. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) food price index has hit record highs in the wake of the war in Ukraine. However, prices were surging well before the start of the conflict due to rising fertilizer and fuel costs, as well as logistical issues. Again, all roads lead back to “E,” or energy security.

In the final analysis, the era of great pretense is over. Putin no longer pretends that he respects sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the Geneva Convention. China’s recent reaffirmation that “China-Russia cooperation has no limits” and its goal of creating a “new, fair, multipolar world order” with Russia leaves no doubt on where they stand. The question is whether Western executives will continue to pretend that it is business as usual with China despite rising geopolitical risks. Granted, reducing their dependency on China is easier said than done – it is a costly multi-year undertaking that will likely lead to less efficiency and higher inflation. Company stakeholders will have to determine if they really care about building sustainable businesses. Some of their Japanese and Korean counterparts – Samsung Electronics, Toshiba, to name a few – have already bitten the bullet and moved their production out of China. If they can, why can’t we?

MORNING IN AMERICA AGAIN

European elites breathed a sigh of relief with French President Macron’s electoral defeat of Marine Le Pen. However, his margin of victory has shrunken from 66% to 34% in 2017 to 58.5% to 41.5%. Le Pen has managed to broaden her appeal despite her association with Putin and the lack of high-profile immigration issues as of late. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a controversial figure known for his pro-Russia/China and anti-EU stance, scored a crushing electoral victory in early April. It’s a sign of popular discontent against condescending elites who have grown out of touch with the concerns of the “deplorables,” to use an American political parlance. These ordinary people’s concerns are closely linked to energy, security, and groceries. The security in this context pertains to their insecurity over jobs, traditional values, and even their identities. It’s the same on this side of the Atlantic Ocean, as populism on both political extremes has been on the rise.

Getting corporations to bring home some of their manufacturing capacity from China will help narrow our inequality and political division. It will likely create a virtuous circle for the economy, society, and investors: more infrastructure-related jobs to lay the foundation, more industrial-strength energy projects for reliable power supplies, more demand on the education system to supply talent, and a very tight job market that should make people welcome immigrants to help enlarge the economic pie. Investors will be salivating at the prospect of greater capital expenditures on automation, engineering, materials, different types of energy (even nuclear), and greater consumer purchasing power.

Importantly, America is exceptionally well positioned for this Main Street ESG of energy, security, and groceries. The U.S. is endowed with shale energy and the wind and sun belts to achieve energy independence. America’s military and power projection remain second to none. We are also blessed with fertile land and agricultural innovation to be the breadbasket of the world. Our strategic weakness is that much of our supply chain is at the mercy of an increasingly hostile China. Let’s get that fixed to make Fortress America truly impregnable.

For more information on Rockefeller Capital Management: rockco.com

This paper is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed, as investment, accounting, tax or legal advice. The views expressed by Rockefeller Global Family Office’s Chief Investment Officer are as of a particular point in time and are subject to change without notice. The views expressed may differ from or conflict with those of other divisions in Rockefeller Capital Management. The information and opinions presented herein are general in nature and have been obtained from, or are based on, sources believed by Rockefeller Capital Management to be reliable, but Rockefeller Capital Management makes no representation as to their accuracy or completeness. Actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated herein. Although the information provided is carefully reviewed, Rockefeller Capital Management cannot be held responsible for any direct or incidental loss resulting from applying any of the information provided. References to any company or security are provided for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results and no investment strategy can guarantee profit or protection against losses. These materials may not be reproduced or distributed without Rockefeller Capital Management’s prior written consent.

Rockefeller Capital Management is the marketing name for Rockefeller Capital Management L.P. and its affiliates. Rockefeller Financial LLC is a broker-dealer and investment adviser dually registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Member Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA); Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC). Rockefeller & Co. LLC is a registered investment adviser with the SEC.

1 Index pricing information does not reflect dividend income, withholding taxes, commissions, or fees that would be incurred by an investor pursuing the index return.

2 Russell Investment Group is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Russell® is a trademark of Russell Investment Group.